The collapse at the end of the war, the revolutions, the establishment of foreign rule over vast territories formerly belonging to the Kingdom of Hungary, and finally the Treaty of Trianon drove several hundred thousand people to leaving their homes. Those who left were looking to continue their lives in rump Hungary. While we lack exact, statistically supported data on the mass of “Trianon refugees,” their numbers likely fall between the figure found in official estimates (ca. 350 thousand) and the one prevailing in the public opinion of the day, which put the number closer to half a million. Estimates by historians today tend to converge around 420-425 thousand refugees. Such summary data, however, fails to represent and relate individual lives, choices and especially the motivations behind the decisions.

The following is an attempt to interpret motivations that once animated those who chose to leave and those who decided to stay. How did they reason – to themselves and to their future readers – about the choices they made? How did they feel about those who made a different choice? And what was it that left the deepest mark on their thinking in the new homeland?

All four authors discussed here hail from Transylvania or its associated parts, and all of them either worked as public employees or had family members who did so. I discuss here one female and three male authors, who all reflected on the events years or even decades after the fact. At the same time, these authors did frequently have recourse to their diaries (whether they admit or not), which dated from earlier, in some cases from the very days chronicled in them. Two of the memoirists had lived in Cluj/Kolozsvár, the other two had dwelt in Arad, a sample that ensures a modicum of depth to the analysis.

One of the Arad authors, Mrs. Helén Karoliny, the wife of Mihály Karoliny experienced what coming under Romanian occupation meant for her city as a homemaker. His husband had worked as the director of the local teacher training institution. She was a Zipser, the descendant of medieval Saxon settlers in Szepes/Spiš, Slovakia, groups of whom had moved to Ruthenia and Transylvania over the centuries. Her narrative style largely assimilated the mainstream strategies of the 1920s of talking about the Trianon experience. She saw both the peace and the Romanian occupation preceding it as a tragedy that endangered the nation, just as it threatened the livelihood of the family.

The Karoliny family had two children attending school in Budapest. This spurred the mother to undertake the perilous journey to the capital and bring the children home – the journey ended with her shepherding home a large number of young Arad inhabitants from the capital. Her narrative paints a self-portrait about a strong-willed woman who is not afraid in the face of danger. The husband barely figures on the pages, and most men whom she encounters during the journey prove to be inept and/or cowards, with a penchant for chasing mirages. The forceful representation of female willpower found in the text need not be explained with recourse to a hidden progressive stream in her thinking. These instances are rounded out by other episodes where she emphasized her “female smarts” and even how she made use of her looks to overcome obstacles in critical moments. British, Serbian and French officers, as well as Swiss diplomats are left wondering in her trail, as she persists in pursuing her mission.

The reasons for the decision to remain in Arad were linked to this journey, as well. The middle-class woman was not a committed anti-Bolshevik. In fact, she observed the first weeks of the Hungarian Soviet with some interest. She had the courage, even in the mid-1920s, to admit in writing that “when I came to [Budapest], I was enthralled by the beautiful principles of communism.” Beyond the experiences in Budapest, material reasons dominated in the decision to stay in Arad. The family felt the wage paid by the Romanian state to the husband constituted a form of betrayal (it was conditional on swearing loyalty to the country), and privately hoped for the triumphant return of Hungarian troops. At the same time, both wife and husband agreed that material want was a greater evil and source of anxieties for them, than making compromises with the powers that be.

For Mrs Karoliny, Romanian rule meant existential fear and social upheaval. She captures the mood of the times in accounts of cheeky servant girls taking openly to stealing, domineering former subordinate schoolteachers, financial insecurity, the arrival of the new Romanian director – a woman – to the teacher training institute and the changes in the appearance of the city. All of these induced the family to leave Arad in September 1920. They headed east, however, rather than towards post-Trianon Hungary: the husband could continue working as the director of another teacher training facility in Cristuru Secuiesc/Székelykeresztúr. The wife, in her memoirs, suggested that the departure did not cause her heartbreak: the city had “become Romanian” and “most of the closer acquaintances had repatriated” to Hungary. Without the right company, a sense of being alienated from the city and riddled with financial worries, their decision was almost a necessity. The sad epilogue to the family’s plight included the early death of their daughter in the year when the husband was dismissed from his new job, as well. After a period of duress, the couple moved back to Arad, where Mrs Karoliny died unexpectedly in 1933.

Dezső Ottrubay, a court judge left Arad in the fall of 1919. He thought of his relocation to Hungarian-controlled territories as temporary, fed by his conviction that Arad could not possibly be awarded to Romania by the peace conference. He arrived to the capital with a single piece of luggage, leaving behind his pregnant wife. As time passed, the mid-career lawyer insisted on remaining in Budapest and refused all potential positions in the countryside. Writing two decades after the fact, it is impossible to overlook the sense of disappointment over how relatives and acquaintances from Arad failed or refused to help him in the process of securing a flat in Budapest. The life of the Ottrubay family there was largely structured by the incessant struggle to reclaim a middle-class lifestyle. Fed by this resentment, the collapse and the revolutions came to signify the rising insubordination of the “lower classes” and the dissipation of solidarity in society. The memoir is remarkable inasmuch as it was composed in a period of increasing radicalization and by a judge who had regularly overseen high-profile, sensitive cases covered in the press, yet its text does not reflect anti-Semitic prejudice, and Jewish figures are often commented on positively. Even Romanians receive acknowledgement occasionally – notwithstanding the mandatory remarks about “Vlach rule”. The author resented, however, those Hungarian colleagues in Arad who had accepted to take the oath of loyalty to the new state and whom he held responsible for having had to leave the city, causing his slide down the social ladder. Finally, one has to remember that Ottrubay, as many others, saw neither the peace treaty, nor the departure from Arad as necessarily permanent. During a period of hardship and failure to find appropriate accommodation, the author’s wife and daughter even returned to Arad for a while. (The sickly daughter, Melinda, went on to become a celebrated prima ballerina two decades later, eventually marrying the duke Pál Esterházy.)

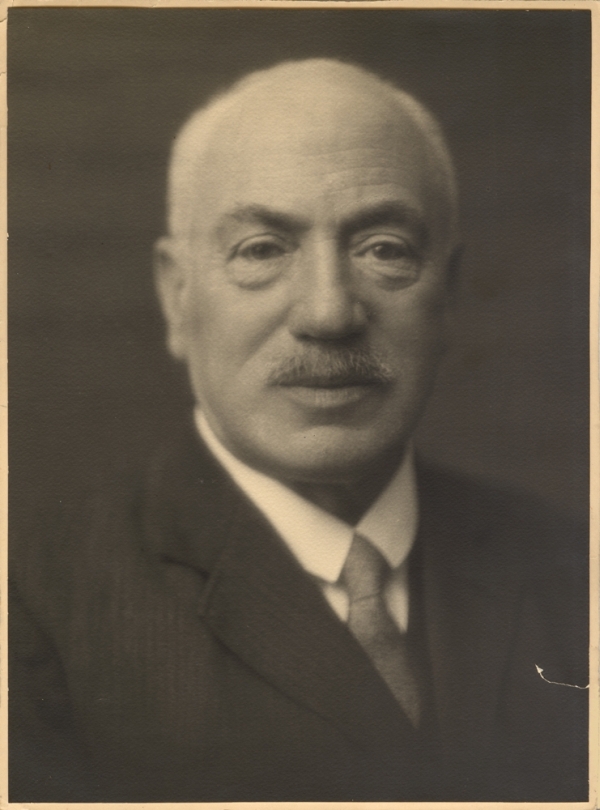

Farkas Gyalui (1866-1952), a library director in Cluj/Kolozsvár was one of those who stayed. His motivations appear more spiritual, but no less clear than those of the previous memoirists. Gyalui was of Jewish origin, but chose in November 1918, in the midst of the collapse, to join the Hungarian Reformed Church. His main motif in doing so was, without a doubt, a sense of loyalty. This feeling of belonging and community of fate extended to the city itself, with the grave of his first wife and that of his son who had both passed away early. However, it clearly centered on the university library which he considered his chief accomplishment and source of pride in life. His superior, for whom he had had little respect and considered a hindrance in his advancement, left the city at the first sign of crisis, but not before Gyalui, as his deputy, had found himself in uncomfortable situations brought about by his indecisiveness. After the departure of the senior director, Gyalui protected the valuables held in the library. The university was closed down, to be relocated, but as its collections were to be left behind, the librarian too decided to stay. The new Romanian administration did not remove him from his position until his retirement in 1926, while also refusing to promote him to the post of library director (with the exception of an interim period). During his brief tenure as acting head of the library, it fell on him to welcome the Romanian royal couple visiting the institution, just as in a different era he had welcomed Zita, the wife to the heir apparent and the future last Habsburg, Charles IV in 1916.

Farkas Gyalui (1866-1952), librarian, historian and author. (Photo: Erdélyi Múzeum-Egyesület / Transylvanian Museum Society)

Gyalui’s vision of history is an idiosyncratic one: he resents Mihály Károlyi and Béla Kun, meaning both shades of the Hungarian Left, but calls out the virulent anti-Semitism of 1919-1920 no less. He disagrees with the official Budapest position about refusing to take the oath of loyalty to the new country, and is dismissive of “fake patriots” who encourage others to stay, while they quit the community and move to Hungary. Gyalui’s ire focuses especially on Emil Petrichevich Horváth, whom he considered an embodiment of all of the above moral vices. It was none other than this repatriated aristocrat who went on to become first a minister of state and then the head of the National Office of Refugee Affairs.

Domokos Asztalos (1875-1973), an officer employed by the Postal Service, chose to leave Cluj/Kolozsvár. His extensive autobiography was preserved in the papers of Miklós Asztalos, his son, a writer, historian, librarian and civil servant working at the Prime Minister’s Office. The father had recently been promoted to postal director when, in January 1919, he found himself dismissed and jobless, since he refused to take the oath of loyalty demanded by the new state. Asztalos first thought about organizing the resistance of his colleagues, but soon found himself isolated with his conviction that the (former) civil servants should stay in Transylvania. A few months later he embarked on the journey to Hungary himself – but not before a detour trying to make a living as a cobbler in his birthplace. In his writing, he lists the conditions of the family, the nervous state of her wife and his worries about his son, Miklós as having played a determinative part in the difficult decision. In this account, financial woes are relegated to a second place. Asztalos was not averse to scapegoating, faulting Swabians (meaning ethnic Germans) for attempting to profit from the population movement, Jews who were seen as pushing them out of country, and his own colleagues who supposedly cared only about their respective financial situations. In the end, the postal officer relocated to Hungary in the last months of 1919, followed by his wife in August of next year. His arrival and the subsequent reset of his career was aided greatly by the informal network established during his time in Cluj/Kolozsvár, which remained operational.

These four life sketches demonstrate that leaving Transylvania – despite all of the conditions pushing the individual towards relocating – was not a straightforward decision. In one case, the “native” Szekler may choose to leave, while the educator, a recent arrival, might opt to stay. One’s situation and standing in life, financial considerations, long-standing opinions and sympathies could all play a part in making the fateful decision. Historical analysis is further complicated by the challenge of having to distinguish between after the fact justifications of these decisions and contemporary considerations that genuinely influenced them. The revolutionary upheaval, lack of familiarity with the new official language, the loss of employment, as well as straightforward expulsion by the new state could all create situations in which leaving became a (near-)necessity. Others stayed out of disgust over either Bolshevism or the White Terror in Hungary or out of fear over losing social status. Interpersonal relations often played a considerable part, as well – be it a resented co-worker or a schemer in the way of advancement. Even the decisions taken by these persons acting as external points of reference could sway choices made by their colleagues. Finally, it bears emphasis that the decisions to leave or to stay were frequently not intended as final and irrevocable. Those who left, did visit Transylvania from time to time, pondering the question of what “loyalty to the nation” – a catchphrase of the era – might mean in such ambiguous times.

Memoirs cited in the text:

Dezső Ottrubay, Memoirs about the World War 1914-1918 and Idem: Years of Hardship after the War, manuscripts, National Széchenyi Library, Manuscript Collections, Quart Hung. 4313

Mrs. Mihályné Karoliny: Memories of Spring 1919 and Idem: After the War, manuscripts, National Széchenyi Library, Manuscript Collections, Fol Hung 3500/1-2.

Memoirs of Domokos Asztalos, Miklós Asztalos Papers, National Széchenyi Library, Manuscript Collections, Fond 301/16.

Farkas Gyalui: Memoirs, 1914-1924. Edited and published by Péter Sas. Cluj/Kolozsvár: Művelődés Egyesület, 2013.