The “invitation manquée” for the Károlyi-government

Hungarian preparations for the peace conference commenced simultaneously with the armistice attempts of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in early October 1918. On the initiative of Count Pál Teleki, leading members of the Hungarian Geographical Society made plans to assemble a large map offering a detailed representation of ethnic groups in the country. The idea was soon proposed to the government, as well. From the side of the Hungarian Central Statistical Office, director László Buday also proposed (in tandem with Teleki) the preparation of “specifically organized statistical selections for the use of the peace conference.” After the October revolution (known as the Aster revolution after the flower pinned on soldiers’ caps replacing the old army symbols), the new government headed by Count Mihály Károlyi provided both financial support and organizational background to the undertaking. A newly formed association, the League for the Protection of the Territorial Unity of Hungary joined the ongoing efforts at the end of the year.

Around the middle of February 1919 – a month after the beginning of the peace conference – the government selected the members of the planned delegation to Paris. The list contained mainly politicians and intellectuals associated with progressive democratic currents: members of the former independence party, liberals, democrats and social democrats. It also included, however, some respected personalities best described as fellow travelers. These latter were only offering their support to the Károlyi government with reservations, and many were to become its opponents eventually. The mission itself was to include Károlyi (as the new President of the Republic), Dénes Berinkey (his successor as prime minister), as well as four cabinet ministers (Barna Buza, Ernő Garami, Sándor Juhász-Nagy, Zsigmond Kunfi), two state ministers (Kálmán Méhely, Zoltán Rónay), a diplomat (Count Imre Csáky), three university professors (Oszkár Jászi, Lajos Lóczy, Gyula J. Pikler), as well as two prominent Transylvanian political figures (Count Pál Teleki, Gábor Ugron). Of the above, Csáky, Teleki and Ugron were known as opponents of the government, who accepted to participate in the effort acknowledging that they shared the official goals with regard to the question of the peace.

The nature of the preparations reflected the democratic and pacifist convictions of the government. Observing the gradual occupation of the country (the Romanian army had reached Cluj/Kolozsvár around Christimas 1918, and Czechoslovak units had marched into Košice/Kassa on 29 December), the cabinet sought to salvage the situation by loyally cooperating with the victorious powers, rather than through accepting the risks inherent in armed resistance. Government members pinned their hopes especially on the peace conference itself. The victorious powers, however, were not planning on issuing an invitation to Hungary, ruled by a government they had not even recognized. As the thinking at the peace conference came to increasingly prioritize political, economic and infrastructural considerations over the ethnic principle, the idea of separating large Hungarian-majority regions from the country proper and incorporating these in successor states gained increasing traction. Instead of an invitation, the Hungarian government received a new diplomatic note on March 20, which established a new demarcation line, permitting the Romanian army to advance up to the Vásárosnamény-Debrecen-Szeged line (by the river Tisza), entering areas with a predominantly Hungarian population.

The “retracted” invitation to the Hungarian Soviet Republic

The aforementioned Vix note led to the demissioning of the Berinkey government in March 1919. It was followed by a coalition of social democrats and communists, who founded the Revolutionary Governing Council and established the Hungarian Soviet Republic. The victorious powers were observing the Soviet with suspicion from its inception. In mid-April, fearing the further spread of Bolshevism, they consented to a new Romanian offensive against Hungary. Simultaneously, however, the peace conference decided to invite the representatives of the Hungarian Soviet to discuss the terms of the peace which had been largely formulated by then and were nearing finalization. The telegram with the invitation was received by the Vienna mission of the Allied and Associated Powers. The mission, however, held back the invitation for fear it would help stabilize the otherwise uncertain situation of the Bolshevik dictatorship. Instead of news of the delivery, Paris received a request for new instructions. The Supreme Council of the peace conference yielded in the end, and did not insist on the delivery of the invitation. The case was simply removed from the agenda. When the Hungarian Red Army commenced its operations against Czechoslovak and Romanian occupying forces, the powers represented at the peace conference came to regard the Hungarian Soviet as an enemy. Their goal was henceforth to remove the Bolsheviks from power. By August 1, domestic dissatisfaction and the renewed offensive of the Romanian forces had led to the fall of the Hungarian Soviet.

During this period, Hungarian peace preparations slowed down, caused in no small part by many of the contributors fleeing from the dictatorship. Parallel to this, Pál Teleki, who was minister for foreign affairs and also for culture in the Arad- and later Szeged-based counter-government led by Count Gyula Károlyi attempted to continue assembling the Hungarian materials for the peace conference. His efforts, however, met with limited success due to the lack of experts.

The belated invitation to the counter-revolutionary government

Peace preparations gained renewed momentum after the triumph of the counter-revolutionary movement. The cabinet formed in the wake of the August 7 coup d’état was led by István Friedrich, the one-time state minister of the war department under Károlyi’s premiership. Friedrich, however, had since moved to the far right, where he had gained the support of various groups. Two weeks after his entry into office, the Peace Preparation Committee was formed (known colloquially as the Peace Preparation Bureau or simply as the Peace Bureau). The new organization had greater numbers at its disposal and continued the work begun earlier in a more structured manner. It was headed by Pál Teleki, who had shown himself to be the most active in the preparation efforts. His deputy, Jenő Cholnoky was entrusted with running Department A, which dealt with questions of a more general nature. The Transylvanian question was handled by Department B, led by István Bethlen.

The participation at the peace conference, however, seemed to be still out of reach. The Allied Powers refused to recognize the Friedrich government, just as they had done with previous cabinets. Only when a new, so-called concentration government was formed, in part at the behest of the British diplomat Sir George Russell Clerk, dispatched to Budapest to help consolidate the political situation, did the disposition of the Allied Powers change. The government formed under the premiership of Károly Huszár on November 24 included all major political groups with the exception of extremist movements. The unfolding stabilization was the outcome of the formation of the wide government coalition, the withdrawal of Romanian troops to areas east of the river Tisza and the entry into Budapest by Miklós Horthy’s National Army. In view of these changes, the peace conference granted official recognition to the Huszár government, and asked, on December 1, that a delegation be dispatched to participate in the signing of the peace treaty.

The council of ministers met at 6 pm on the same day and decided to accept the invitation. Foreign Minister Count József Somssich was asked to present the final list of the delegation’s members at the next government conference. It was also agreed that each party would be permitted to nominate a member to the mission, who would join its ranks as a political councillor.

The decision that the delegation would be chaired by Count Albert Apponyi had been made prior to the formal invitation. The decision, however, had not been uncontested at the time, and remained controversial later on, as well. The reason for this was that many saw Apponyi as a symbolic and highly visible figure of nineteenth-century politics and of historic Hungary. At the time, he was perhaps the most respected statesman of the country who could represent historic Hungary with the greatest credibility. Those who disagreed with this nomination tended to do so for the exact same reasons why others supported it: his role in the pre-War political regime. In fact, some influential participants of the peace conference felt his appointment to constitute a provocation: was the delegation to be led by the very politician who had sponsored the assimilationist and anti-minority 1907 Education Act and who had supported the Austro-Hungarian declaration of war against Serbia in summer 1914? French diplomacy was especially active in trying to prevent Apponyi from joining the conference in Paris. After weeks of discussion, however, the victorious powers chose to accept the decision of the Hungarian government.

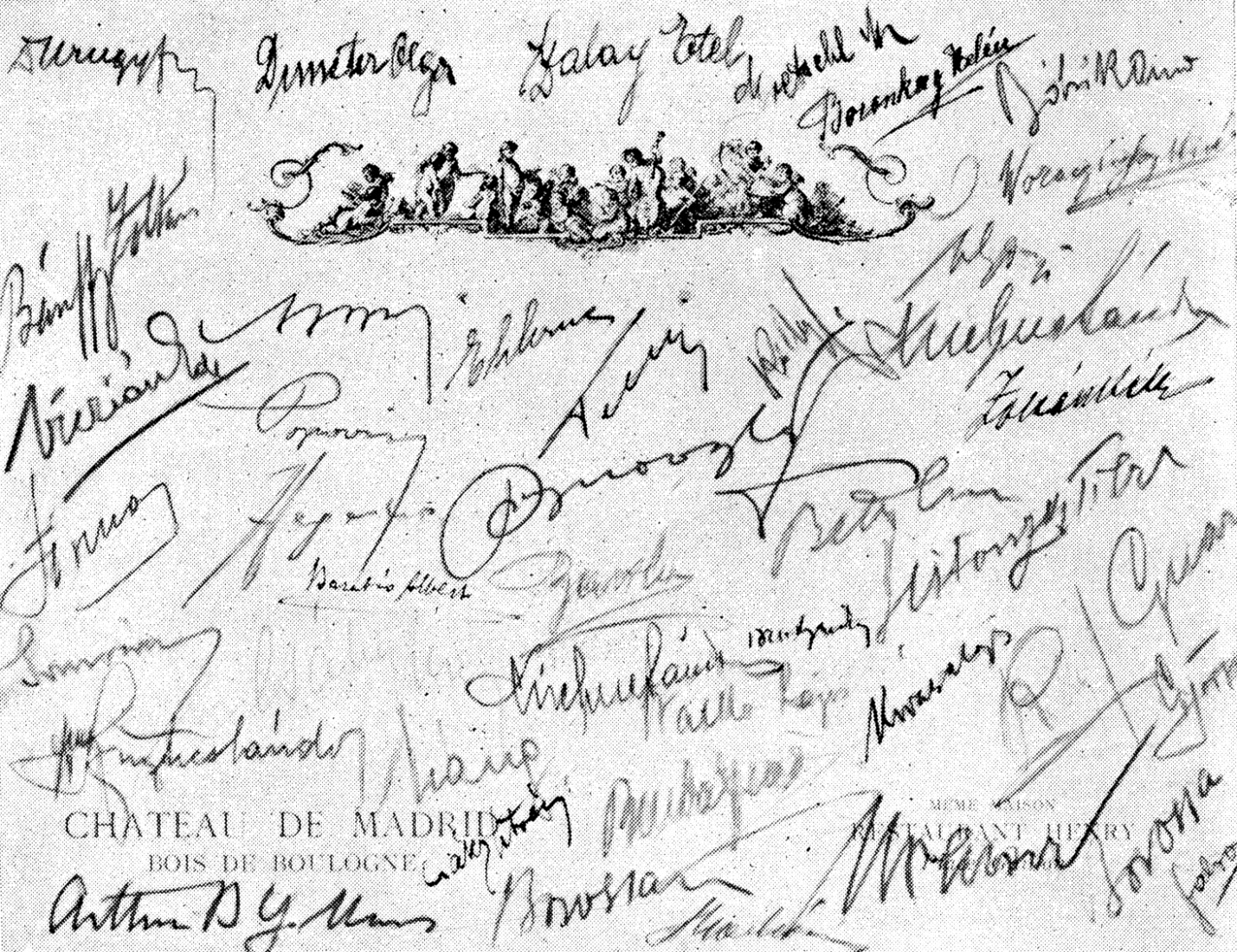

Signatures by members of the delegation to the peace conference on a menu card of Restaurant Henry, at the hotel Château de Madrid, where the delegates were accommodated (January 8, 1920). Source: Dezső Zelovich: Fabro, az újságíró-gyorsíró. [Fabro, the journalist-stenographer] (Library of Hungarian Standardized Stenography Vol. 94) Budapest: Gyorsírási Ügyek M. kir. Kormánybiztossága, 1935. p. 14.

The delegation had the appearance of being an imprint of old Hungary in other ways, as well. The legates came without exception from the ranks of the political, diplomatic, military, economic and cultural elites. Their views tended to be conservative, with some members harboring liberal conservative sympathies. Their nationalism had been reinforced and strengthened by the experiences of the Great War and the subsequent revolutions. The main (and overrepresented) strata in the delegation were the politically active segment of the aristocracy and the state bureaucracy, where public servants from the nobility tended to outweigh commoners. The senior positions were all filled by middle-aged males. Younger men – delegates in their 20s or 30s – usually worked in support roles. The seven female members were limited to secretarial tasks, working as typists and stenographers, and remained excluded from the meetings. Even during meals, the women sat at a separate table.

On January 5, 1920, the train carrying the delegation pulled out of Keleti Grand Station, heading to Paris. It was a special train that took some effort to assemble, including salon, travel and buffet cars deemed sufficiently elegant for the purpose. The reason for this was that the occupying Romanian forces had been seizing Hungarian railroad cars en masse. The delegation was seen off by a great crowd of people, and the departure ceremony even included addresses by both Prime Minister Károly Huszár and Albert Apponyi as the chairman of the delegation. For its members, as numerous memoirs attest, the experience of travelling form Budapest towards Hegyeshalom (on the Austro-Hungarian border), was an emotional and uplifting experience. At every station, a cheering crowd welcomed the train rolling in. Local notables delivered speeches of encouragement and hope, and it was Apponyi who responded everywhere by expressing gratitude, but also warning against excessive optimism and urging a sober assessment of the situation.

The train had a passenger list of 66. Apart from Apponyi, the chairman, it included 5 commissioners-general (Count István Bethlen, Baron Vilmos Lers, Sándor Popovics, Count József Somssich and Count Pál Teleki), six commissioners (Richárd Bartha, Count Imre Csáky, Tibor Kállay, Emil Konek, Baron Boldizsár Láng, Lajos Walko), three experts (Lóránt Hegedüs, Elemér Jármay, Tibor Scitovszky), a secretary-general (Iván Praznovszky) and his two deputies (János Wettstein, Ernő Hauer), as well as ten diplomatic secretaries (Baron Zoltán Bánffy, György Barkóczy, Arno Bobrik, Count István Csáky, Sándor Ezry, Sándor Kirchner, Sándor Kiss, Károly Ottrubay, Béla Török, Emil Walter, Count Olivér Woracziczky). The auxiliary personnel comprised six office staff, six typists and stenographers, four junior office aides, four printers, five railwaymen, a staff of six for the buffet car, as well as the seven journalists of the press service (Jenő Benda, Samu Boros, Miksa Bródy, Henrik Fabro, Sándor Krisztics, György Ottlik, Dezső Saly). Beyond the initial contingent, two further commissioners-general, Iván Ottlik and Béla Zoltán, as well as five experts (Pál Bíró, Tibor Gerevich, Alajos Kovács, Károly Maslowski, Ede Viczián) and several couriers were dispatched to the quarters of the mission in Neuilly and attached to the delegation over time.

For the delegates, the work undertaken and the experiences gathered proved to be determinative with regard to their future careers. Considering only those who became cabinet ministers in later years, the list includes the future Prime Ministers István Bethlen and Pál Teleki (who also held other cabinet posts), as well as six ministers (Imre Csáky, István Csáky, Hegedüs, Kállay, Scitovszky and Walko). Five more delegates went on to serve as envoys or as heads of diplomatic missions (Bobrik, Kiss, Praznovszky, Wettstein, Woracziczky). Their progress through the diplomatic ranks was accelerated in a way reminiscent of the careers of some interwar Hungarian politicians who had joined the counter-government in Szeged. As is well-known, Horthy, himself minister of war in the Szeged government and, as a former naval officer, lacking a large network and familiarity with Hungarian political life, held himself to the practice of picking prime ministers from among his one-time counter-revolutionary allies. Delegation members accomplished something similar in the way they went on to dominate the Foreign Ministry for many years (Teleki: 1920, 1920–1921, Imre Csáky: 1920, Scitovszky: 1924–1925, Walko: 1925–1930, 1931–1932, István Csáky: 1938–1941). Similarly, the ministry of finance was led at various points in time by three different members of the peace mission (Hegedüs: 1920–1921, Walko: 1921, 1924, Kállay: 1921–1924). One of them even went on to head the Ministry for Trade (Walko: 1922–1926).

The sojourn in France affected the delegates in two important ways. They experienced the thrill of intensive and selfless teamwork, about which Apponyi reminisced in a foreword (for a book published at the end of 1920) : “a miracle happened in Neuilly, one worthy of our affection and one that we hope to re-live on a grander scale here: about sixty Hungarians were lumped together, yet there was no dissent, fighting or internal competition, nor hatred and intrigue, nor self-promotion – in fact, with selfless devotion to the holy purpose, mutual affection and respect, every member of this group did what he had to, from the leaders down to the printers and office keepers (these, our humbler colleagues were often terribly overburdened with urgent tasks), all of us lived only for what was our shared duty and all performed whatever their position called for.”

The other, perhaps even more important experience was the realization of helplessness into which the defeat in the war and the dissolution of the historical state had cast the nation. For most delegates, this arose from sensing, for the first time, the dominance of great power intentions over the weakness of small states. This led many to believe – as they were prone to mention thereafter – that a gigantic task awaited Hungarian society: that of restoring the self-confidence of the badly shaken nation, of stabilizing and strengthening the country that had been labelled guilty for the war, while becoming diplomatically isolated and economically weakened, as well. The future process of consolidation, they felt, was to provide the foundations for the revision of the peace treaty into which they had placed their hopes.