Presentations given in the various panels covered more than the single wartime year in the conference title, encompassing the broader context of the global conflagration. Topics ranged from intimations of the impending war in literary works to the peace planning processes and the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy. The participants, representing almost the whole of Europe, laid out research findings in English, German or Slovenian.

The first day opened with welcome addresses from senior university leadership and organizers. Speakers included Branka Kalenić Ramšak, Špela Virant, Mira Miladinović Zalaznik, Irena Samide, Tanja Žigon from Ljubljana (http://www.ff.uni-lj.si), as well as Florian Kührer-Wielach from Munich (http://www.ikgs.de). The keynote was delivered by Clemens Ruthner (Dublin), titled “Labs of the Apocalypse”: The End of the World in German-Language Horror Literature around World War One, highlighting the darker moods of the era through a survey of German-language science fiction and horror literature. This apocalyptic strand of literature, largely forgotten by posterity, prefigured many radical choices of later ages in its reflections on social, political, economic and other crises of the early 20th century, as well as the World War.

The first panel (Visions of War and Peace) included a presentation by Milka Car (Zagreb), titled Utopias and Freedom Projections in the Collection of Novellas: „Croatian God Mars” by Miroslav Krleža, which focused on the effect of the war and leftist revolutionary ideology on the author’s oeuvre. In the same section, Eamonn O’Ciardha (Derry) gave a talk under the title Arthur Griffith, Sinn Féin and „The Resurrection of Hungary”: Ireland and Hungary: Comparative, Imperial Contexts, an examination of the inspiration that Hungary’s special status with the dual monarchy meant for the Irish national movement. His paper, surveying political literature of the era and accounting for the admiration directed toward Hungarian nationalists, provided additional nuance to our understanding of the loss of Hungary’s prestige that occurred in the West European countries in this period – largely as the outcome of the unjust nationalities policy of the Hungarian state under the dualist system.

The second panel, Between Utopia and Reality, opened with a talk by Anja Urekar Osvald (Maribor), titled From „Michel”, „Aunt Germania” and „Nibelungenland”: Visions and Utopias in the Historical German Press in Lower Styria and their Transformation /1900–1917/. The paper offered a glance into the problems and anxieties of Austro-German communities in Slovenian-majority areas, representing an instance of German borderland discourse. It revisited the German “Michel” and the sisters “Germania” and “Austria” in the broad allegory that enjoyed popularity in the era. Beyond criticisms of “Vienna”, “Budapest” was repeatedly referenced as the positive example in this border discourse (for similar reasons as in the previous case: the relative strength of assimilationist and nation-building policies). Johann Lughofer (Ljubljana) presented his paper A journey through the „Heanzenland” with Joseph Roth, analyzing a transient but highly characteristic end-of-war phenomenon, the temporary “state” of the Republik Heinzenland. This short-lived quasi-state of Germans living in Western-Hungary and chronicled by Joseph Roth in a series of articles helped Lughofer highlight some of the difficulties that arise when regional and local identities – such as that of the Heinzen/Heanzen of Western Hungary – become the object of homogenizing efforts by nationalizing forces that seek to fit them into modern national identities.

The third panel (Political Visions and Utopias I.) opened with the talk by Gorazd Bajc (Maribor–Trieste) titled British Experts in Their Analyses of the Powder Keg that was the Upper Adriatic, 1916–1919. Bajc evoked the painstaking work done by British advisors to the actual architects of the peace at the post-war conference. Almost two hundred small publications and papers dealt with the region, offering a pragmatic and to the point survey of the various dilemmas and controversies. The analyses extended as much to historical legacies, and statistical problems of the present as it did to future outlooks. The picture that emerges suggests that the experts pursued objectivity in their work, produced balanced evaluations and based their proposal on these. Their goals came into conflict with power political, economic and strategic interests – Realpolitik in short – and the latter tended to triumph in the end. Ljubinka Toševa Karpowicz (Rijeka) delivered a presentation titled The State of Fiume – The Italian National Council /from 23 November 1918 to 16 September 1920/. The paper shed new light on the working of the Free State in the light of the protocols of the Italian National Council. This quasi-state is distinguished by its relative resilience: it existed from November 1918 to January 1924. During this time, the informal governing body, the Council engaged with numerous challenges: it got rid of the former Hungarian civil service, inserted itself into the tobacco trade and financial transactions, as well as some of the more traditional diplomatic activities. Our group’s researcher, Csaba Zahorán (Budapest) contributed the final paper of the panel, titled Utopias in the Shadow of Catastrophe: The Idea of Szekler Self-determination after the Fall of Austria-Hungary. The talk dealt with what could have become another quasi-state, yet never materialized: the potentiality of a Szekler Republic. At the end of 1918, Hungarian elites opted for remaining loyal to the historical Kingdom of Hungary, and in January 1919 the Romanian army took Árpád Paál, a proponent of an independent Szekler state into custody, nipping a local conspiracy in the bud. Szekler statehood remained virtual – existing only as an idea, laid out by Paál in a pamphlet. The text survived among his papers and was analyzed by Bárdi Nándor as a reflection of the multi-decade crisis of the region and the utopian thinking that characterized the wartime years.

Ljubljana from the Nebotičnik

The second day of the conference began with the second part of the same panel, Political Visions and Utopias II. Andrei Cuşco (Chişinău) presented his paper A Failed Experiment? The Bessarabian Elites between Autonomy, Federalism and Nationalism /1917–1918/, which treated the region at the cross-section of Romanian nation-building and Russian imperialism. Cuşco took up once more the question of regional identities, highlighting the conflict which pitted the nationalist and the social agendas against each other towards the end of the war. His paper was one of several to direct attention to the number of alternatives that opened up, at least temporarily, to peoples, states and various other communities. For Bessarabia, union with Romania was one option amongst several others. The outcome was not an a priori given, or a necessity, as many later interpretations have suggested. Nataliya Nechayeva-Yuriychuk (Chernivtsi) introduced another quasi-state, the Hutsul Republic of the Ukrainian Subcarpathian region (National Identity and Its Role in State-Building: The Hutsul Republic Experience). The Hutsulschina, which was declared as a state in November 1918 in Yasinia (Kőrösmező) sought accession to the Western Ukrainian Republic, but found itself in the crossfire of several conflicting national interests. Beyond the Ukrainian national movement, Hungary, Romania and Czechoslovakia all laid claim to its territory, which was inhabited mainly by the Hutsul, a Ruthenian community native to the Carpathian region. Its existence of about six months was ended by the Romanian military, which moved to occupy it in June 1919, only to cede control of the area to the Czechoslovak state soon afterwards. Rudolf Gräf (Cluj-Napoca) discussed a similarly multi-ethnic region, the Banat in his talk titled The End of the World War I and the Attempts at Redesigning the Banat Politically. The Banat, inhabited by Romanians, Germans, Serbs, Hungarians and others was also claimed by several states, which led local leaders, mainly ethnic Germans, to consider the idea of proclaiming an independent republic. The presentation highlighted also that supranational ideas could compete at times with various nation-building concepts, as could various socialist-type political notions – notwithstanding the fact that national and nationalizing state-building did end up carrying the day.

France Martin Dolinar’s lecture (Between Expectations and Political Reality: The Bishops of the Metropolitan Archdiocese of Gorizia during and after World War I) opened the section on the history of religion titled Ecclesiastical Visions Within and Beyond New Political Borders. He focused on the history of the so-called Illyrian archdiocese which was first established in 1828. The territories under the archbishop had always been multi-ethnic in character, yet this did not prevent either the clergy or the majority of the faithful to remain loyal to the Habsburg Monarchy up to the end of World War I. Quite to the contrary, the archbishops were expressing their dissatisfaction with regard to the distrust towards the Southern Slav elements, characteristic of both Germans and Hungarians. In the end, the Italian occupation of the area in fall 1918 ended both Austro-Hungarian rule and the Southern Slav aspirations. In his presentation tracing the history of the archdiocese up to its dissolution in the 1930s, Dolinar demonstrated how the newly arrived Italian authorities also intervened in ecclesiastic affairs. Pál Lackner (Budapest) focused on the history of Protestantism in Austria and Hungary through an analysis of the Lutheran churches and the structural changes they underwent in the wake of World War I. In his paper titled „From Brother to Neighbour – and the Other Way Around?” Relations between the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Hungary and its Former Parts Lackner traced the series of splits that yielded 14 Lutheran churches in 7 states in the place of the four pre-war churches of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy. These changes could have important effects on the individual churches: Lutherans in Hungary had made up 12% of the population in 1910, yet within the 1920 borders their share fell to 6%. Oleh Turiy (Lviv) investigated how the Greek Catholic Churches, born out of the respective religious unions of Brest, Uzhhorod (Ungvár) and Alba Iulia (Gyulafehérvár) centuries prior, slowly came to function as platforms of national ideologies. So much so, that even their loyalty to the Habsburg dynasty, which had founded and supported them in the hope of creating forces of integration, wavered ever more frequently (Between Ecclesial Identity, National Commitment and Political Loyalty: Church Structures of Uniate Ruthenians after the Fall of the Habsburg Monarchy). In closing, Heiner Grunert (Munich) discussed the thinking of Serbian Orthodox leadership about the post-war order in a talk titled „The Symbols of Our Liberation, Unification and Resurrection”: Visions and Historical Concepts of Serbian Orthodox Circles at the End of the Great War. Grunert pointed out that the war brought about the deterioration of the relationship between the dualist state and the Serbian orthodox population. Internment, hostage taking and strict supervision – added to other suffering caused by the war – led to the interpretation of the final phase of the war as the Serbian Golgotha, which was to be followed by the sacred moment of resurrection. In the heady days of December 1918, expectations of “fraternity, peace, unity of mind, love and prosperity” prevailed for a time, but the hopes, plans and, ultimately, illusions were followed by disappointment on many counts in the subsequent years.

The conference also included reflection on the 500th anniversary of the Reformation, and the final panel was accordingly dedicated to the previous centennial commemorations (1917 – The 400th Anniversary of the Protestant Reformation). Botond Kertész (Budapest) delivered his presentation (War and Celebration – Observations of the 400th Anniversary of the Protestant Reformation in Hungary) about the interplay of the then ongoing war and the commemorations. Many of the latter were held on the frontlines, by Lutheran soldiers and surprisingly few of them were cancelled, notwithstanding the circumstances. Wartime ideology did penetrate the events, however. While the enthusiasm of the early days of the war had been long gone, the Reformation understood as struggle and its eventual triumph was nevertheless represented as prefiguring the eventual German-Hungarian triumph. Lajos Szász (Budapest-Leipzig) continued the survey in his talk titled The Reformation Jubilee 1917 in Hungary and Transylvania: Concepts and Plans for the Future. Szász highlighted that adherents of the Reformed Church (Calvinist protestants) were especially fervent patriots and expected a short war ending with victory in the summer of 1914. They also believed in the mission of the Monarchy, “bringing light” to the dark corners of the Balkans. It was only after the 1916 Romanian entry into the war and the invasion of Transylvania that the expansionist ideology gave way to concerns about the situation in Hungary itself. While nationalist discourse was radicalizing, linking Hungarian identity, Calvinism and chauvinism, the idea of the reunification of the two large Protestant churches was raised once more. The concluding presentation by Tanja Žigon (Ljubljana) observed in her talk The Year 1917 in the „Slovenian” Lands of Austria-Hungary, in View of the 400th Anniversary of the Reformation the regional specificities of commemoration. These local events were very different from the ones seen in Germany – as a result of the Austrian counterreformation and one could even say that larger events were not taking place – despite the memory of the “Slovenian Martin Luther”, Primož Trubar, whose work and memory was also presented in the paper.

Angela Ilić, representing the Institute for German Culture and History of South Eastern Europe in Munich, summarized the presentations during the concluding discussions, highlighting the dichotomy between local autonomous actions and the chief trends of global history. She observed that while the social, ethnic, religious and other initiatives discussed in the presentations often came to naught, and the many quasi-states proved to be transient, their histories nevertheless permit important insights. These include the causes and contexts of these failures, but also the relationships into which they were embedded, making them worthy subject matter for research that offers potentially important rewards.

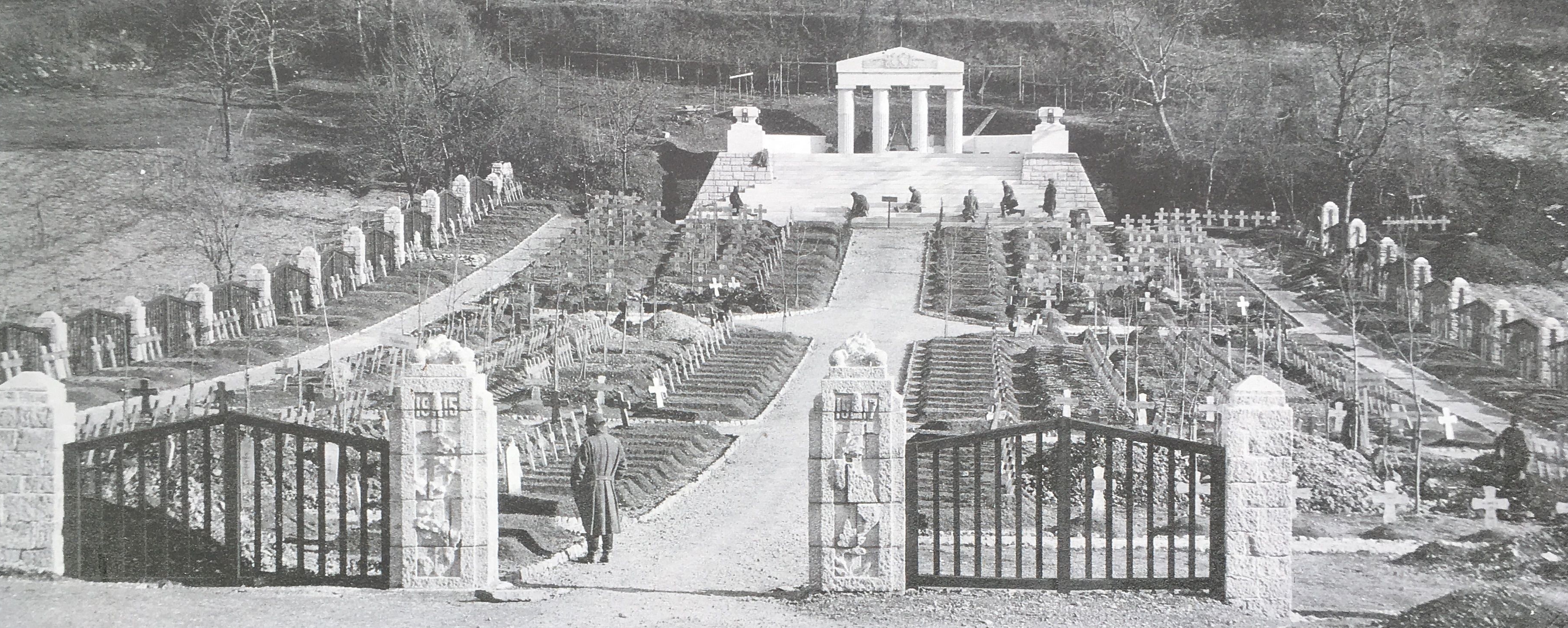

The organizers and the local branch of the Goethe Institute sponsored the closing dinner of the conference in Lubljana castle, where participants were shown the exhibition With Luther into the World of Words before dinner. The next day, a fascinating excursion was offered to Štanjel, a picturesque small town on the Slovenian Karst Plateau, including a visit to the military cemetery from World War I.

The military cemetery in Štanjel

The military cemetery in Štanjel on an archive picture

website of the project: https://insungewisse.wordpress.com/